THE ORIGINS OF KYOKUSHIN KARATE

KYOKUSHIN, AN ANCESTRAL MARTIAL ART

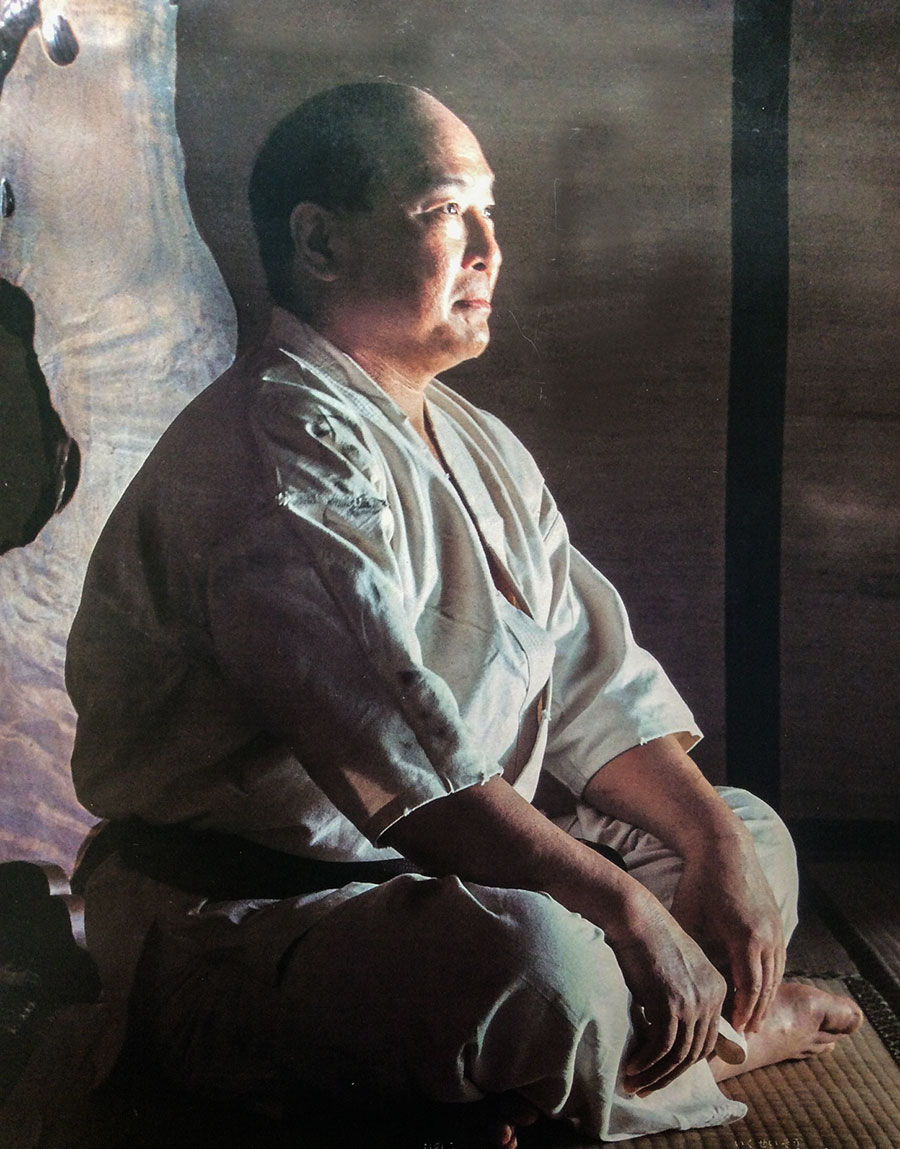

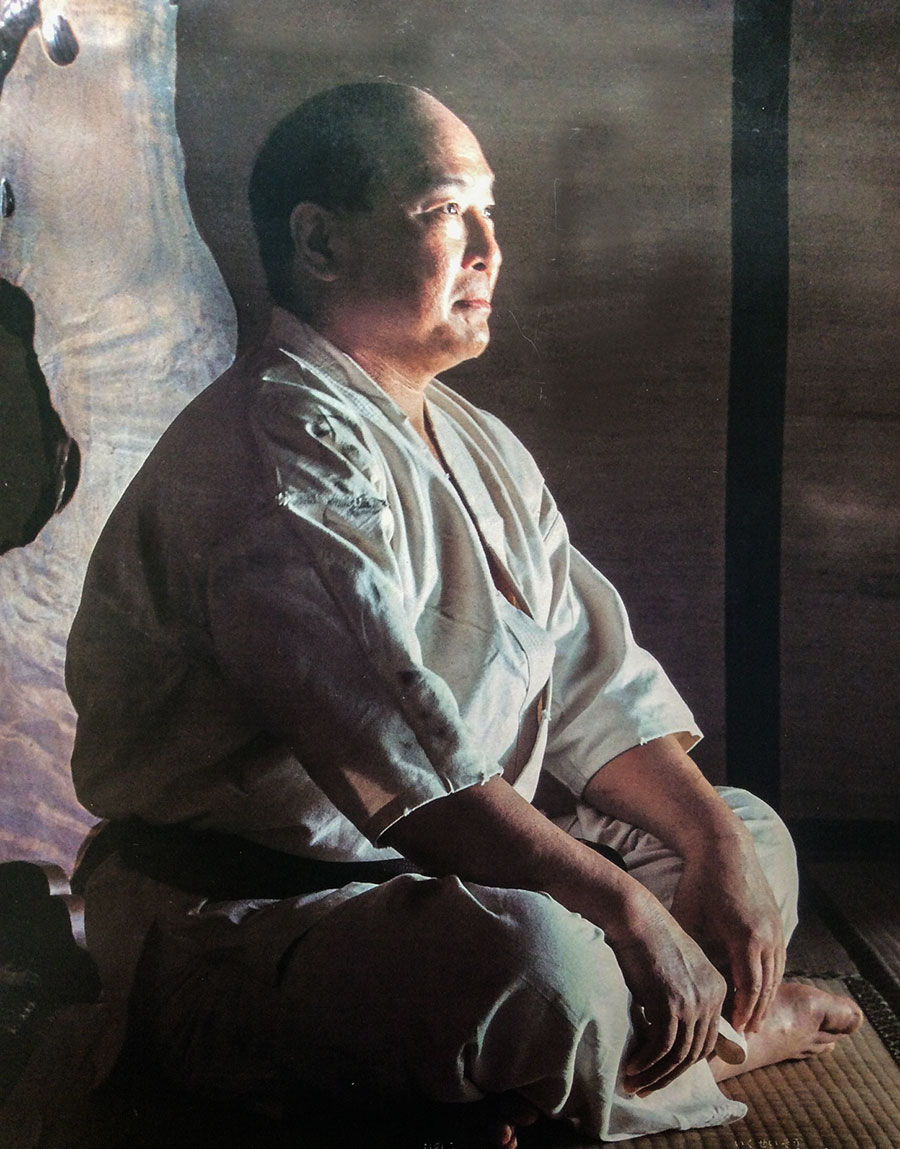

Kyokushin karate: a martial art created by Masutastu Oyama

Oyama’s story still has many question marks.

I’ve done a lot of research into the history of Masutastu Oyama and the origins of Kyokushin karate, and there are many questions that remain unanswered.

It is often the case when the origins of a personality are shared between two countries, especially when those two countries have a long-standing rivalry. Masutatsu Oyama, with his Japanese and Korean roots, is no exception. Depending on the sources and their origins, his life takes different turns. I have therefore directed my research with the understanding that some information may be vague or even contradictory.

Sensei Michel Angers

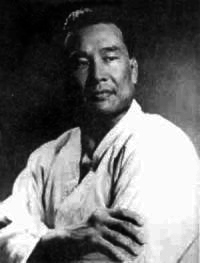

Masutatsu Oyama was born on July 27, 1923, in South Korea.

Originally named Yong-I Choi, he changed his name to Oyama a few years later when he immigrated to Japan. This name was not chosen at random, as it means “great mountain.” But Oyama’s travels across Asia were far from over. Shortly after settling in Japan, he began studying martial arts at the age of 9. He pursued these studies under a family friend who taught him Kempo and traditional Korean martial arts. After mastering the basics of these arts, Oyama quickly immersed himself in more advanced techniques, learning Gōjū-ryū from Yamaguchi Gogen on his family’s farm.

Years spent in China.

These three years in China were surely the beginnings of what would inhabit him for his entire life: the search for absolute truth. At 12 years old, when he returned to Korea, he continued his learning with Korean Kempo, also known as Taiken or Chabi. But his journey did not stop there. Just after arriving in Korea, he returned to Japan, this time to stay longer. His passion for martial arts continued to assert itself. A passion he even studied at Takushoku University, where many karateka and judoka have passed through. It was at the university that Oyama began taking judo classes. His abilities were impressive, and in four years, he reached the level of 4th dan. He combined these judo classes with learning Shotokan karate, particularly thanks to Gishin Funakoshi, considered the father of modern karate. This strong connection pushed him to excel. His mastery of Shotokan was also certified during his university years when he obtained the level of nidan (black belt, second dan) at just 17 years old. Three years later, two additional dans were added, bringing him to yondan (4th dan).

Retreat to Mount Minobu.

The continuity of martial arts learning involves deep meditation and reflection. That is why he exiled himself at 23 years old, with the aim of creating Kyokushin karate in the Minobu Mountains, with only a book on the exploits of the great samurai Miyamoto Musashi and Yashiro, his companion for this adventure. Unfortunately, his companion abandoned him after six months. The solitary Oyama had only Mr. Kayama as a contact, who provided him with the bare essentials. This idea of exile did not arise by chance in Oyama’s mind; it was, in fact, the result of initial discussions with So Nei Chu, an expert in gōjū-ryū.

His ambition to meditate for three years, however, was not achieved; he ended it after 14 months. During these long months, he received written encouragement from So Nei Chu, his mentor and instigator, who also suggested that he shave one eyebrow. This suggestion, which he followed, motivated him not to return to civilization so that he would not have to show himself with a face sporting only one eyebrow.

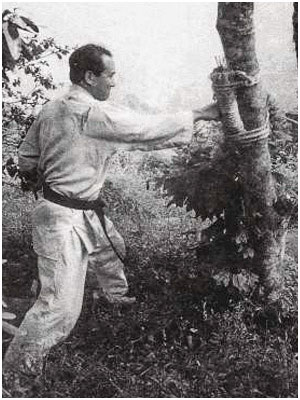

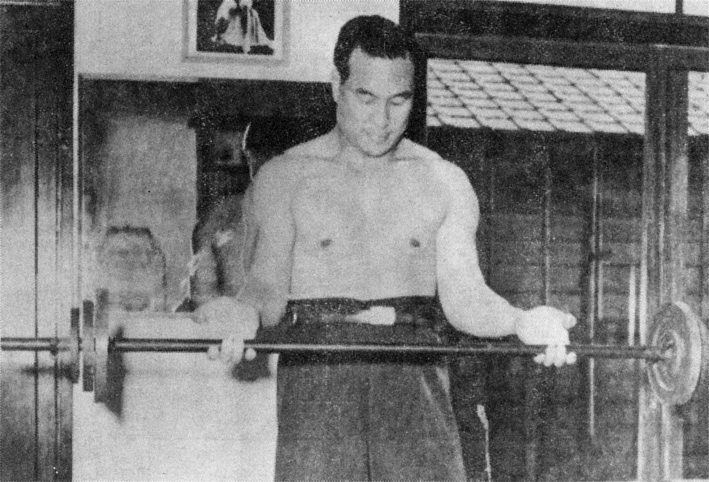

That same year, at 24 years old, he participated in the First Japanese National Martial Arts, where he won the championship title with honors. Once these titles were achieved, he decided to exile himself once again, this time for 18 months, on Mount Kiyozumi. During this retreat, he dedicated himself entirely to self-improvement. The days were repetitive and consisted solely of training. It was an extremely demanding program that allowed for rest only at night. Amid the intensity of the exercises, Oyama focused on studying Zen and philosophy. It goes without saying that he continued his studies in martial arts, always keeping in mind the creation of Kyokushin karate (even though the official name had not yet been chosen at that time).

This rigor in learning would be Oyama’s spearhead and his true hallmark for Kyokushin Karate. He draws particularly from the ancient Korean arts he discovered from a young age. He embodies the traditional kicks while adding new leg attacks and destructive sweeps. At the end of this second exile, Oyama returns to civilization, full of confidence and sure that he has understood the meaning of his life. It is in 1950, at the age of 27.

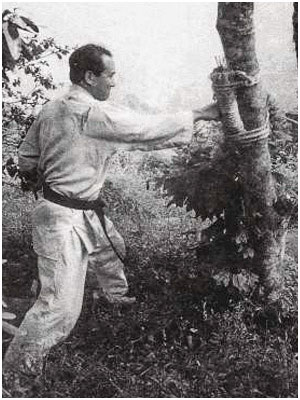

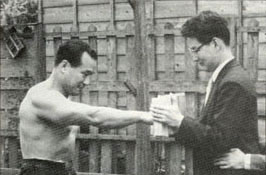

To prove himself even further, he takes on the challenge of facing a bull. He encounters his first one in 1950, the first of a long series, as he would go on to face more than 50 bulls, killing three of them. This controversial practice often sees him simply breaking the bull’s horns with a devastating strike. Eager to demonstrate his superiority and more motivated than ever, he challenges all the masters in Japan, including masters of kendo, aikido, judo, and karate. He defeats them all. In 1952, he continues to prove his supremacy during a tour in the United States, facing over 270 opponents, most of whom he defeats with a single punch. The fights are swift, with the best opponents managing to hold their ground against Oyama for only a few minutes. These tours create the legend of Oyama. Every strike he delivers is decisive, aimed solely at breaking his opponent. A blocked punch could result in a broken arm, and a missed block could lead to broken ribs. The nickname “Godhand” is naturally given to him, which comes with a very telling motto: “Ichi geki, Hissatsu,” literally “With one strike, death is certain.” Despite all these victories, Oyama is not invulnerable, and he suffers an injury in 1957. It is a serious injury that immobilizes him for six months.

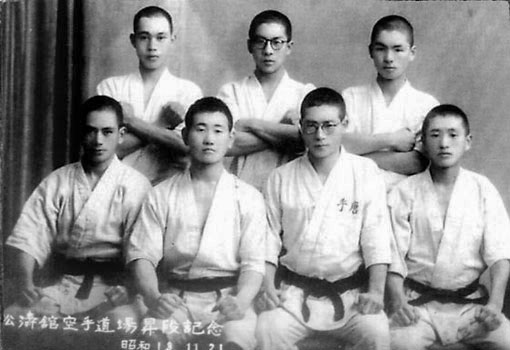

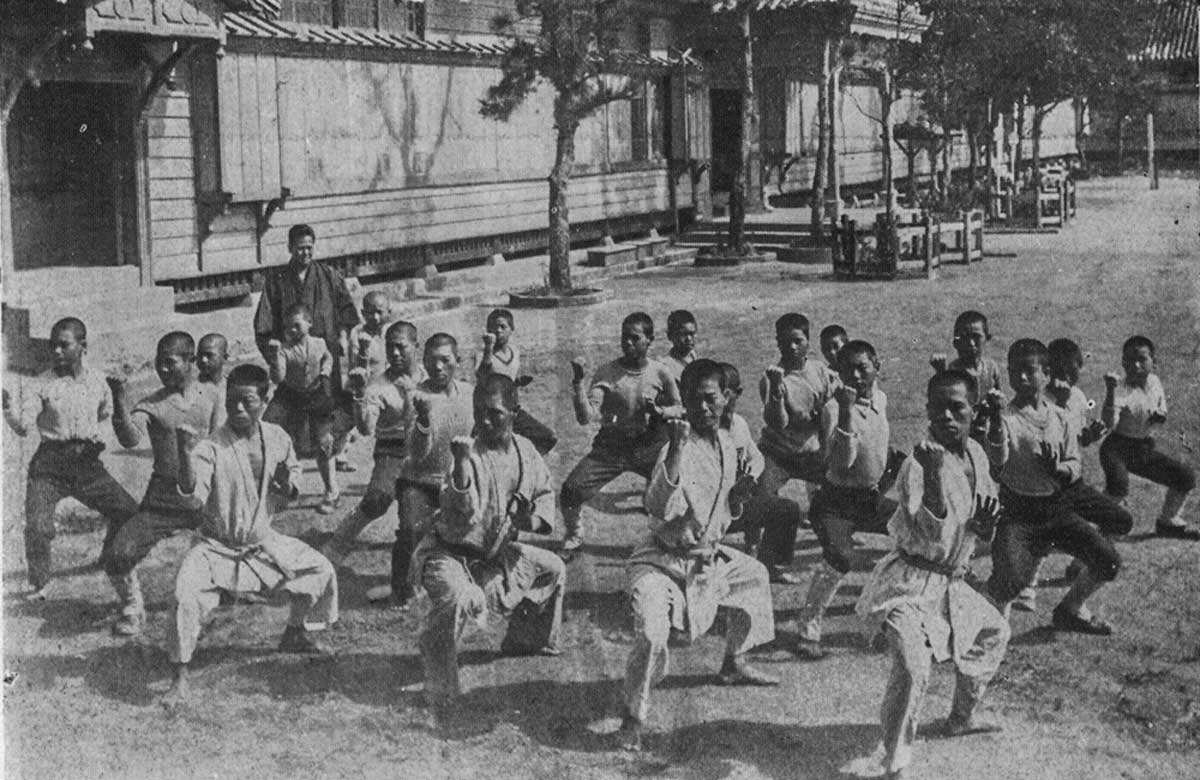

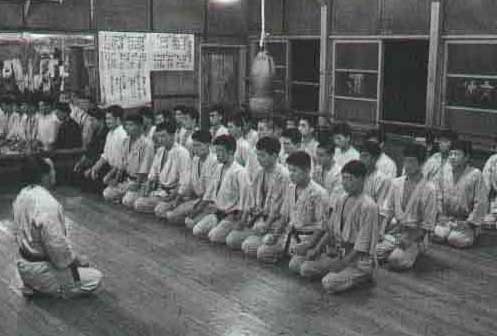

Opening of the first dojo and creation of the Kyokushin style of karate.

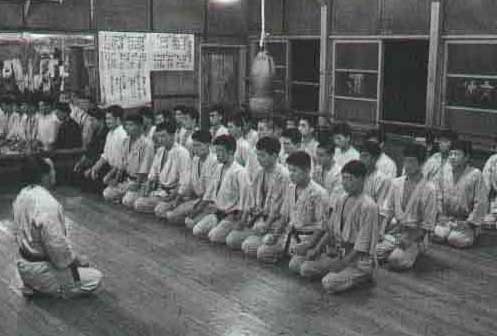

After reaching the heights of martial arts, Oyama took on a new mission: to pass on his knowledge and values. The idea of opening a dojo was born in 1953, which he executed with an outdoor dojo that trained many disciples. In 1956, his first indoor Kyokushin karate dojo was inaugurated.

Kyokushinkai, or Kyokushin long remained a discipline practiced only in Japan. Shihan Bobby Lowe was the first to export it in the 1960s, specifically to Hawaii in the United States, where the first dojo dedicated to this art was established. This is the honbu dojo. It was only at this point that Oyama decided to give his style of karate a name: kyokushinkai. which means “school of ultimate truth.” This art is primarily based on Japanese karate, emphasizing effectiveness. It is a full-contact karate that Oyama embodies and further develops according to his vision of combat.

The export of Kyokushin karate was facilitated by Oyama’s tours around the world, but also significantly through the publication of books and encyclopedias. In Vital Karate, Masutatsu Oyama encapsulates the essence of his thirty years of study and training. He then composes a comprehensive encyclopedia consisting of three volumes: What is Karate, This is Karate and Advanced Karate. In these works, he elevates the analysis of Kyokushin karate to a higher level and details all its aspects.

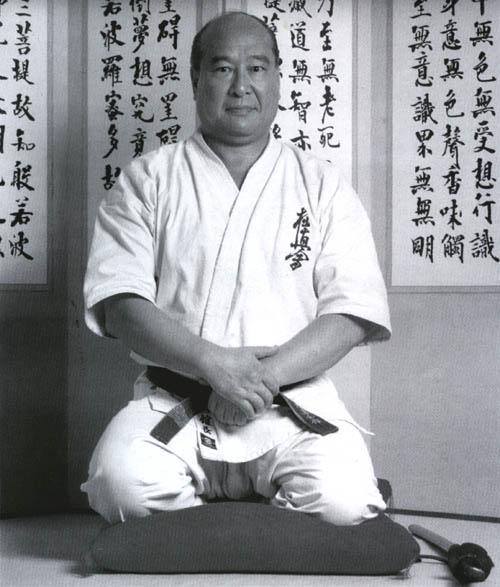

Masutatsu “Sosai” Oyama passed away on April 26, 1994, at the age of 70 from lung cancer. Following his death, the apparent unity among his disciples fractured, revealing numerous factions. Some remained loyal to the original organization (International Karate Organization “IKO”), while others established their own organizations.

Legend has it that Sosai was fully aware of this and even premeditated this discord to ensure that the entirety of his work would be attributed to him and that no one could carry it on.

The foundations of Kyokushin karate

Kyokushin karate is a synthesis of several forms of martial arts, including Judo, Shotokan, and Goju-Ryu. It stands out for its focus on combat effectiveness, combining direct and powerful strikes. The motto of Kyokushin is “One strike, one victory.”

Gōjū-ryū inspires its punching techniques and breathing work. It draws from Shotokan the basic principles of linear movement and adds, for higher ranks, the circular forms of Taikiken from Master Kenichi Sawai.

Kyokushin karate has given rise to over twenty combat styles. Among the most well-known are Mejiro Kick Boxing (after the challenge from Muay Thai masters and the departure of one of Oyama’s students) and Kudo Daido Juku (created by another student of Oyama).

For the toughest of his karate practitioners, Master Oyama established a test that anyone can attempt whenever they wish—Hyaku Nin Kumite, the challenge of one hundred fights.

The term Kyokushin means “Ultimate (kyoku) Truth (shin),” representing all those who seek to attain the ultimate truth. This is also what the inscription, the Kenji, on the front of the dogi (uniform) signifies.

The symbol of Kyokushin karate is the kankū, which originates from the kata Kanku. Kankū literally translates to “Contemplate the sky.” This kata begins by raising open hands with the thumbs and index fingers touching. Attention is then directed toward the center of the hands to unify the mind and body. The tips of the kanku represent the fingers and signify purpose. The thick part represents the space between the hands and signifies infinity and depth. The inner and outer circles represent continuity and circular movement. The Japanese calligraphy of the word kyokushinkai is reproduced on the dogi of members of this karate style worldwide. These characters were originally painted by Sensei Haramotoki, a grand master of calligraphy and a friend of Sosai Oyama.

Kyokushin karate, the most demanding style.

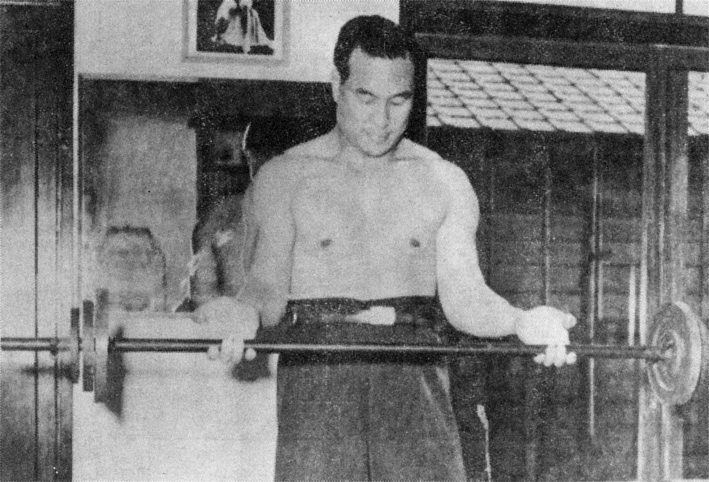

Kyokushin karate is viewed as the physically toughest and most demanding form of karate, while also being the most effective. It is an art that relies on advanced combat techniques, requiring practitioners to maintain exceptional physical conditioning. Self-defense is both effective and realistic in this style.

Even though the physical aspect is heavily emphasized, the development of the mind is also paramount. In fact, it is the foundation of kyokushin. The martial art is built on these essential pillars, namely a developed intellect and a continual spiritual quest. Without these, kyokushin lacks meaning; it all revolves around self-control and mastery of one’s mind. This brings peace and provides the practitioner with calm and serenity, allowing them to direct their energy as they see fit. This tranquility is also the basis of respect, both for oneself and for others.

Destabilizing one’s opponent and potentially making them fall is the main goal of kyokushin. To achieve this, strikes to the legs and sweeps are essential. The combat is close-range, allowing for these destructive blows. A kick can be countered with a direct punch.

While fighters must be physically sharp, they also need to be tough and resilient. Their endurance and limits can be pushed through work on their qi. This use of qi requires a great mastery of internal strength and a lot of learning time but allows certain parts of the body to become very resistant. This is why kyokushin practitioners do not wear gloves or other protective gear after long training phases.

Master Oyama defined combat as follows: “The karateka’s counterattack must be instantaneous. It should be done with a sudden relaxation and an immediate return, like the action of a snake.”

With over 25 million practitioners spread across 130 countries Kyokushin karate is one of the most popular styles of karate in the world.

All rights reserved, Kyokushin Karate Saint-jean-sur-Richelieu, sensei Michel Angers

KYOKUSHIN KARATE

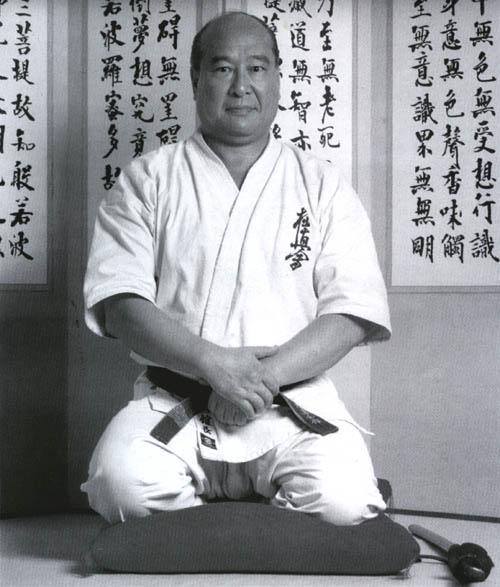

Kyokushin karate: a martial art created by Masutastu Oyama

The story of Oyama still raises many questions.

I’ve done a lot of research into the history of Masutastu Oyama and the origins of kyokushin, and there are many unanswered questions.

This is often the case when a personality’s origins are shared between two countries. Even more so when the two countries are long-standing rivals. Masutastu Oyama, with his Japanese and Korean origins, is no exception to the rule. Depending on the versions and their origins, his life takes different turns. I therefore wrote these texts bearing in mind that some information may be unclear or even contradictory.

Sensei Michel Angers

Masutatsu Oyama was born on July 27, 1923 in South Korea.

Originally called Yong-I Choi, he changed his name to Oyama a few years later when he emigrated to Japan. A name far from chosen at random, since it means “great mountain”. But Oyama wasn’t done wandering around Asia. As soon as he settled in, Oyama began studying martial arts at the age of 9. He completed his studies with the help of a teacher close to his family, who taught him Kempo and ancient Korean martial arts. Having mastered the rudiments of these arts, Oyama quickly immersed himself in more advanced techniques, learning Yamaguchi Gogen’s göjü-ryü on the family farm.

Years spent in China.

Those 3 years in China were surely the beginnings of a lifelong quest for absolute truth. When he returned to Korea at the age of 12, he continued his apprenticeship in Korean Kempo, also known as Taiken or Chabi. But his journey did not end there. Having just arrived in Korea, he returned to Japan, this time to stay longer. His passion for the martial arts continued to grow. It’s a passion that he goes on to study at Takushohu University, where many karatekas and judokas have studied. It was at the university that Oyama began taking judo lessons. His skills were impressive, and in 4 years he reached the level of 4th dan. He combined these judo lessons with Shotokan karate, thanks in particular to Gishin Funakoshi, considered the founding father of modern karate. A strong connection that drives him to excel. His mastery of Shotokan was also certified during his university years, when he obtained the nidan level (black belt, second dan) at just 17 years of age. 3 years later, two more years were needed to obtain the yondan level (4th dan).

Retreat to Mount Minobu.

Continuing to learn the martial arts requires meditation and deep reflection, with the aim of creating Kyokushin karate. This is why, at the age of 23, he went into exile in the Minobu Mountains, with only a book on the exploits of the great samurai Miyamoto Musashi and Yashiro, his companion on this adventure. A companion who unfortunately gave up after 6 months. The lonely Oyama’s only contact is Mr. Kayama, who provides him with the bare essentials of life. This idea of exile didn’t mature by chance in Oyama’s mind; it was in fact the fruit of an initial brainstorm with So Nei Chu, an expert in gōjū-ryū.

His ambition to meditate for three years, however, was not achieved; he ended it after 14 months. During these long months, he received written encouragement from So Nei Chu, his mentor and instigator, who also suggested that he shave one eyebrow. This suggestion, which he followed, motivated him not to return to civilization so that he would not have to show himself with a face sporting only one eyebrow.

That same year, at the age of 24, he took part in the First Japanese National Martial Arts, where he won the title of champion with honors. After winning these titles, he decided to go into exile once again, this time for 18 months, on Mount Kiyozumi. During this retreat, he devoted himself entirely to perfecting his skills. The days follow one another and are made up entirely of training sessions. An extremely demanding program that only allows rest at night. In addition to the hustle and bustle of the exercises, Oyama devotes himself to studying Zen and philosophy. Needless to say, he continues his martial arts studies at the same time.

This tough approach to learning was to become Oyama’s spearhead and his true trademark. He was particularly inspired by the ancient Korean arts, which he discovered at an early age. He personified traditional kicks by adding new leg attacks and destructive sweeps. At the end of this second exile, Oyama returned to civilization, full of confidence and sure of having understood the meaning of his life. This was in 1950, at the age of 27 (the name Kyokushin karate was not yet in use).

To prove his point, he challenged himself to a bullfight. He faced his first bull in 1950. The first of many, he faced over 50 bulls, killing 3 of them. A controversial practice, he is usually content simply to break the bull’s horns with a destructive blow.

Eager to show his superiority and more motivated than ever, he challenged all the masters of Japan, including kendo, aikido, judo and karate. He defeated them all. In 1952, he continued to prove his supremacy on a tour of the United States. He defeated over 270 opponents, most of them with a single punch. The fights were fast-paced, with the best opponents keeping Oyama at bay for just a few minutes. These rounds created the legend of Oyama. All his blows are decisive, with the sole aim of breaking his opponent. A blocked blow and the arm was broken, a failed block and the ribs were broken. The nickname “Godhand” was naturally bestowed upon him. Godhand was even given a catchphrase: “Ichi geki, Hissatsu”, literally “with one blow, death is certain”. Despite all these victories, Oyama was not untouchable, and an injury struck him in 1957. A serious injury that immobilized him for 6 months.

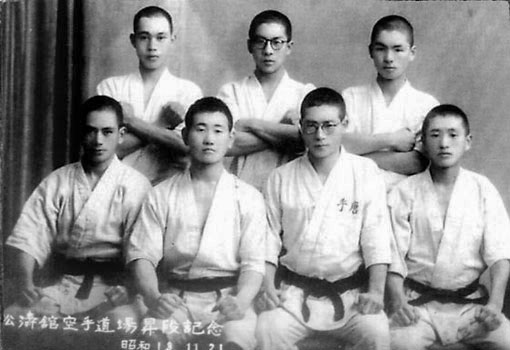

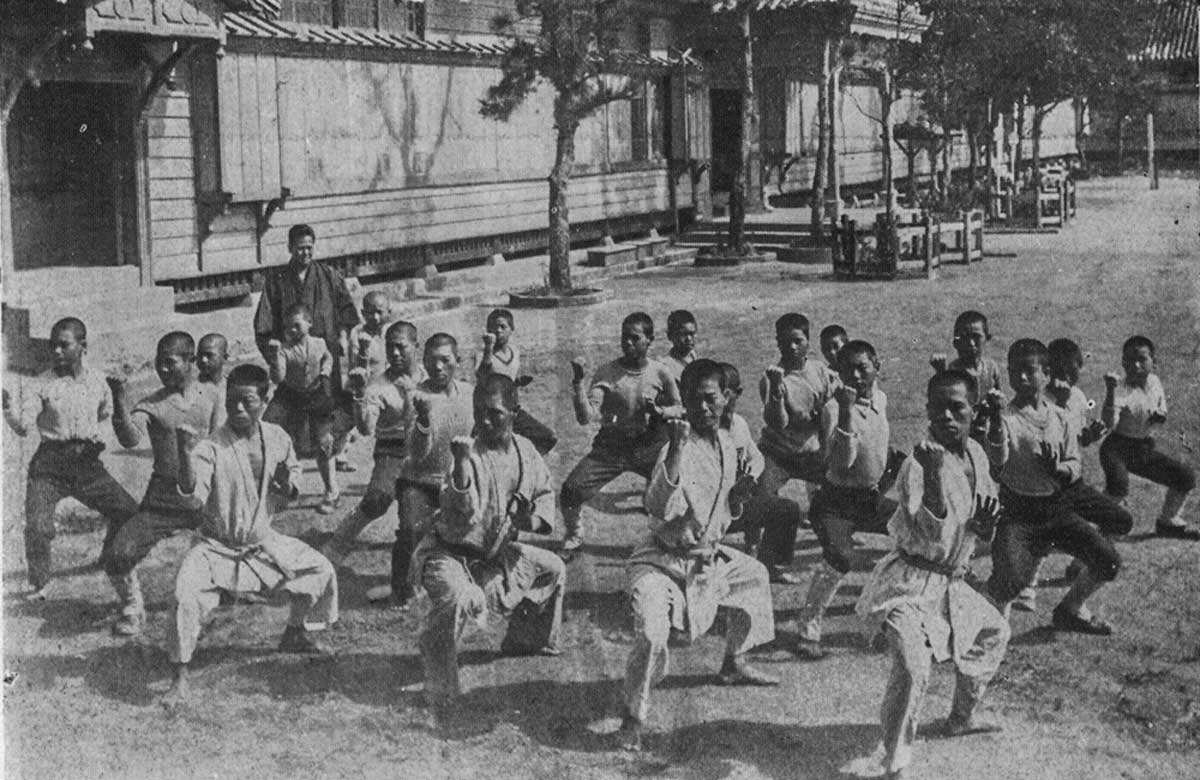

Opening of the first dojo and creation of the Kyokushin style of karate.

Having reached the pinnacle of the martial arts, Oyama has set himself a new mission. To pass on his knowledge and values. The idea of opening a dojo was born in 1953, an idea he carried out with an open-air dojo that trained numerous disciples. In 1956, his first Kyokushin karate hall was inaugurated.

For a long time kyokushin karate was only practiced in Japan. Shihan Bobby Lowe was the first to export it in the 60s. More precisely, in Hawaii in the United States, where the first dojo dedicated to this art was created. It’s the honbu dojo. It was only then that Oyama decided to give his style a name: kyokushin karate. A name that means “school of ultimate truth”. This art is essentially based on Japanese karate, which insists on efficiency. A full-contact karate that Oyama personifies and develops even further, according to his vision of combat.

eThe export of Kyokushin karate happens through Oyama’s tours around the world, but also a lot through the publication of books and encyclopedias. In Vital Karate, Masutatsu Oyama writes down the essence of his thirty years of studies and training. He then composes a true encyclopedia made up of three volumes: What is Karate, This is Karate and Advanced Karate. In these, he takes the analysis ofKyokushin karateto a higher level and details all its aspects.

Masutatsu “Sosai” Oyama passed away on April 26, 1994, at the age of 70 due to lung cancer. After his death, the apparent unity among his disciples divided and revealed many different factions. Some remained loyal to the original organization (International Karate Organization Kyokushin “IKO”), while others created their own organizations.

La légende dit que Sosai était pleinement conscient de cela et avait même prémédité cette discorde pour s’assurer que l’intégralité de son œuvre lui soit attribuée et que personne ne puisse la poursuivre.

The foundations of Kyokushin karate

Kyokushin karate is a synthesis of several forms of martial arts, including Judo, Shotokan, and Goju-Ryu. It stands out for its focus on combat effectiveness, combining direct and powerful strikes. The motto of Kyokushin is “One strike, one victory.”

Gōjū-ryū inspires its punching techniques and breathing work. It draws from Shotokan the basic principles of linear movement and adds, for higher ranks, the circular forms of Taikiken from Master Kenichi Sawai.

Kyokushin karate has given rise to more than twenty fighting styles. Among the most well-known are Mejiro Kick Boxing (after the challenge from the masters of Muay Thai and the departure of one of Oyama’s students) and Kudo Daido Juku (created by another student of Oyama).

For the toughest of his karate practitioners, Master Oyama established a test that anyone can attempt whenever they wish—Hyaku Nin Kumite, the challenge of one hundred fights.

The term Kyokushin means “Ultimate (kyoku) Truth (shin).” This represents all those who seek to attain the ultimate truth. It is also what the inscription, the Kenji, on the front of the dogi (uniform) signifies.

The symbol of Kyokushin karate is the kankū, whose origins come from the kata Kanku. Kankū literally translates to “Contemplate the sky.” This kata begins with the hands raised, open, with the thumbs and index fingers touching. Attention is then directed toward the center of the hands to unify the mind and body. The points of the kankū represent the fingers and signify purpose. The thick part represents the space between the hands and signifies infinity and depth. The inner and outer circles represent continuity and circular movement.

The Japanese calligraphy of the word kyokushin is reproduced on the dogi of members of this karate style around the world. These characters were originally painted by Haramotoki Sensei, a grand master of calligraphy and friend of Sosai Oyama.

Kyokushin karate, the most demanding style.

Kyokushin karate is seen as the physically most challenging and demanding form of karate, while also being the most effective. It is an art that relies on advanced fighting techniques, requiring practitioners to have exceptional physical conditioning. Self-defense in this style is effective and realistic.

Even though the physical aspect is heavily emphasized, the development of the mind is also paramount. In fact, it is the foundation of Kyokushin karate. The fundamentals of this martial art rest on these essential pillars: a developed intellect and a perpetual spiritual quest. Without these, Kyokushin karatehas no meaning; it all revolves around self-control and mastery of the mind. This tranquility brings calm and serenity to the student, allowing them to direct their energies where they choose. This peace is also the basis of respect, both for oneself and for others.

sss

Unbalancing one’s opponent and potentially knocking them down is the main goal of kyokushin karate. To achieve this, strikes to the legs and sweeps are essential. The combat is close-range, allowing for these destructive blows. A kick can be countered with a direct punch.

While fighters must be physically sharp, they must also be tough. Their endurance and limits can be pushed through work on their qi. This use of qi requires a great mastery of internal strength and a lot of learning time, but it allows certain parts of the body to become very resilient. This is why kyokushin practitioners do not wear gloves or other protections after long periods of training.

Master Oyama defined combat as follows: “The karateka’s counterattack must be instantaneous. It should be done with a sudden relaxation and an immediate return, like the action of a snake.”

With over 25 million practitioners spread across 130 countries Kyokushin karate is one of the most popular styles of karate in the world.

All rights reserved: Karaté Saint-Jean-sur-Richelieu

220 Saint-Louis Street, Suite 101

Saint-Jean-sur-Richelieu

info@karatesaintjean.com

Phone: 514-464-8125

All rights reserved Michel Angers – Kyokushin Karate Saint-Jean-sur-Richelieu

Member of the Canadian Federation of International Kyokushin Karate

https://karatekyokushin.ca/

220 Saint-Louis Street, Suite 101

Saint-Jean-sur-Richelieu

info@karatesaintjean.com

Phone: 514-464-8125

All rights reserved Michel Angers 2018 – 2022 – Kyokushin Karate Saint-Jean-sur-Richelieu